Let’s Talk About Pompeii

Posted: September 17th, 2010 | Author: Devon | Filed under: Italy | 2 Comments »

I’m fascinated by Roman ruins. While in England, I seriously considered driving eight hours to go see the chest-high remnants of Emperor Hadrian’s wall. I’ve snapped many photos of distant crumbled piles of stone, told that they were of Roman origin. When we changed trains in Rome, from our seats I could see an old dome and a piece of the aqueduct. This made me giddy as a child. But walking the streets of Pompeii, the best preserved of all Roman cities, is a magical experience that left me in awe of those ancient people.

It’s difficult for me to pinpoint my interest in Roman times. There’s the schoolboy fascination with superlatives: biggest civilization, biggest army, most land, most cultural influence, etc, etc.

What impresses me most, I think, is that things they created still exist today. That level of engineering, creating structures that have stood for two-thousand years, boggles my mind. Rome today STILL uses portions of the sewage system built before the birth of Christ, and it works fine. Then consider their limitations: No electricity. No motors. No power tools or steel or gasoline. I thought building that little staircase was hard. Imagine the Colosseum. In our travels across Italy, in old villages and along ancient Roman roads (now major highways), I’ve squinted my eyes and tried to imagine what it was like back then. It’s difficult. So much is gone and so little left. Piles of mossy rocks are far from evocative, so I’m forced to depend on my ill-equipped imagination. I picture 2-dimensional Hollywood b-roll with pancake makeup actors in populating cardboard sets. There’s no sense of “being there.”

Which is why Pompeii is an incredible place. Simply put, you are there. The roads and walls, the art and advertisements — they all stand today, near identical to their appearance at the height of the Roman empire. A walk down their roads is a literal walk through history.

Pompeii was a mid-sized, “average” Roman city in 79 A.D. One morning in August, the volcano Mount Vesuvius blew open, burying the city in hot ash and embers. In the picture below, connect the two sides of the mountain in the distance to form a triangle. That’s what Vesuvius used to look like. Of the 20,000 that lived here, 2,000 didn’t make it out in time. They, and their city, were locked away beneath this ash until the 1700’s, completely untouched by the centuries of weather, war, and invaders that destroyed nearly every other city from this time. Excavations began in the 1800’s and continue to this day (a quarter of Pompeii has yet to be excavated).

At the front gates, there are hooks to tie up boats, though the sea coast is now a mile away. Two-thousand years of silt build up and tectonic movements are responsible for that. The main plaza has city hall, a courthouse, a temple to Jupiter (the main god), and a market hall. The four main elements of Roman life are represented: government, justice, spirituality, and commerce. Citizens voted here and this is where the two main roads out of town converged.

We followed Rick Steves’ walking tour of Pompeii. It seems to be a popular one (we saw several copies of his book there), so you may have heard of a few of these sites.

High sidewalks run along roads paves with basalt. In some areas, the roads have flecks of white pottery embedded in them, to aid those traveling at night. The roads are flooded with water to clean them, so raised stepping stones are used at intersections for pedestrians to cross the road. These stones are a standard width, to accommodate chariot traffic, which used had a standardized axel size. The DMV has ancient roots. This also boggles my mind. Chariots! Like in Ben-Hur! Two-thousand years ago, and this massive empire had a central chariot axel authority. Who thought of this? Who enforced it? There were probably chariot inspectors who worked middle-management jobs in government their entire lives. Not emperors, but not slaves in a field either. These were people, similar to those I know today.

Grooves had formed in the basalt from chariot traffic. This really hit it home to me, that people lived here. They look like fresh tire tracks in mud, as though someone had just passed through earlier today in their standardized chariot. Again: Chariots!

There’s the public baths. These were essentially the gym. You had a workout area, outdoors. A cool bath, warm bath, and hot bath. A steam room with hollow walls, where hot air was pumped to warm the room. The arched ceiling was grooved, not just for looks, but to collect condensation and lead it in rivulets down the sides into a collection trough. Romans didn’t like water dripping on them in their steam room, so they engineered a solution. I love it.

The solid marble fountain in the steam room had inscribed into it the name of the sponsor (the guy who paid for the fountain) and the amount he paid for it. We saw these public proclamations in a few places around the city: the central plaza, the amphitheater, public water fountains. These men wanted recognition, so they put their names on a plaque — just like today.

A few things were different from how it is in the states. A few blocks from the “Cavec Anem” House (“Beware of Dog” house, named for the detailed floor mosaic in its entrance that shows a dog and the words ‘Cane Avem’), in the “nice” neighborhood, is one of the thirty brothels in Pompeii. It’s sits on a street corner, near a bakery, just like any of the other local vendors. You enter to a hallway with five small rooms, each with a bed made of stone, complete with stone pillow. Above the doors are illustrations of various sexual positions — a kind of menu. The women are large and pale, and the men trim and a dark red (supposedly this indicates the men are horny). There’s even a little toilet at the end of the hall.

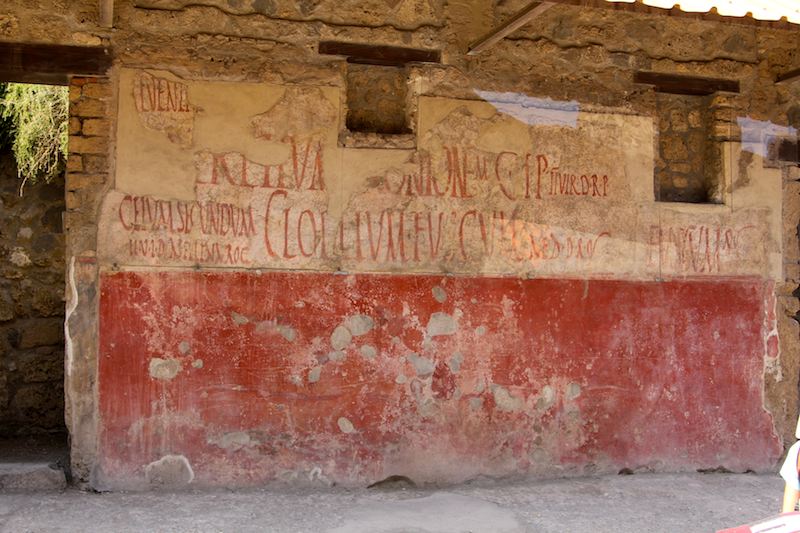

There’s tons more: three different water systems that could be shut down in order of importance (most important: the public fountains); the home of the rich brothers, with the marble safes permanently affixed to the floor; the ornate table inscribed with the name of one of Julius Caesar’s assassins, likely sold at auction after he was executed and now here in Pompeii; fast food restaurants with holes for pots and a groove in the doorway where an accordion-style door was run when the shop was opened and closed; the amphitheater, still standing (I walked through the center and imagined the thousands it could hold); the handwritten signs in Latin, red ink on the walls of shops; brass water taps in the shape of a bull’s head; grand marble columns “faked” with brick and plaster (people were trying to save a buck, even back then).

It all adds up to the realization that ancient people and modern people are strikingly similar. Though we’re separated by the ages, we share so much of what makes us human. They had families and jobs and loves and problems and lines at the DMV and all the other pieces of a life. We have a few niceties (hygiene, human rights for more people, all that science) but the basic needs (waste removal, water, economy, governance and order) are the same, and being met in essentially the same way. It makes history more relatable. At Pompeii, you go beyond simply “being there”, like an intruder in an idealized imagined past. I drank water from their bull-head taps, walked their streets, and visited their homes. For a few hours, I lived in Pompeii.

Once again, thank you, thank you, for taking me on your trip with you via your photography and writing. Simply amazing.

I’ve been following this blog for a few weeks now. Joe Doughtery turned me on to it. I visited Italy 2 years ago and you’ve retraced a few of my steps…..really enjoying it. Great blog; thanks for taking us along. Victoria